Subscribe to Aimee's MFA Lore Newsletter using this LINK and get 2 months of full access for free!

MFA Lore: Your Essential Writing Resource

.png)

The blog posts here represent a small sample from my Substack publication, MFA Lore, where I share the wealth of insight that I’ve gleaned over more than four decades of publishing and teaching creative writing at the MFA level.

Why MFA Lore? I know there’s some dispute about the value of graduate degrees for writers who “just want to write.” I shared that hesitation for years, publishing more than three novels and four nonfiction books before getting my own MFA at Bennington. But the knowledge and community I gained at Bennington, followed by 15 years of teaching MFA students at Goddard College, ignited my writing life and improved my work in too many ways to count. My goal here is not to motivate you to get an MFA (unless you’re so inclined, of course) but to give you the essences of an MFA education--mius the tuition!

To Make Your Writing More Memorable...

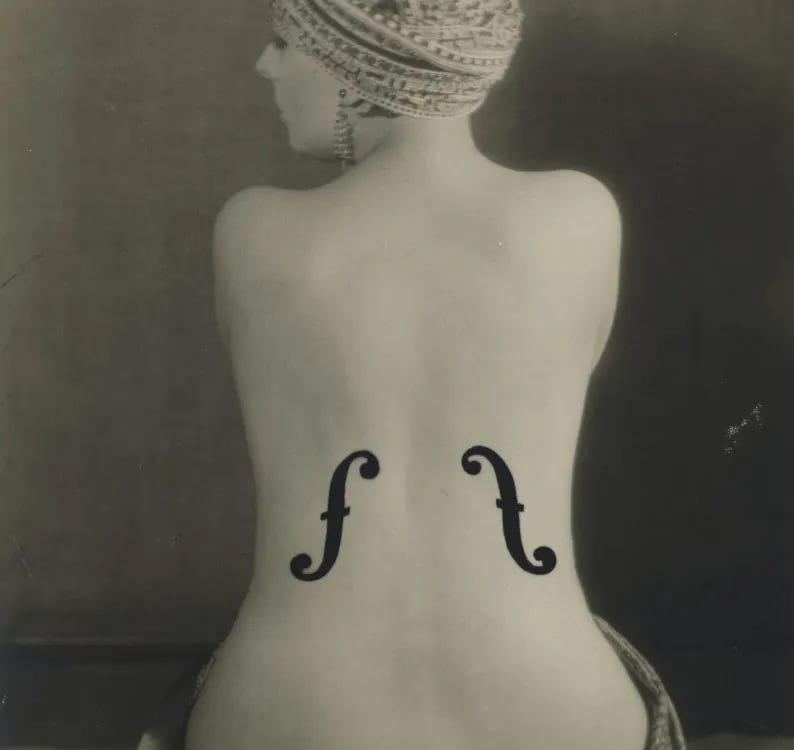

I tripped across a fascinating study the other day that offered an essential nugget of scientific insight for writers, and I want to share it with you here.

Yale researchers have been studying the “stickiness” of memory:

The human brain filters through a flood of experiences to create specific memories. Why do some of the experiences in this deluge of sensory information become “memorable,” while most are discarded by the brain?

They used a computational model and behavioral study using visual imagery to answer this question. Subjects were shown a rapid series of pictures, then asked to recall them. It turns out, the most memorable scenes were the ones that didn’t immediately make sense.

For example, a picture of a bright red fire hydrant deep in the woods would be easier to remember than an image of a bunch of deer bounding through the same forest. A mountain with a clown standing on the summit is more memorable than a peak with a climber planting a flag. A beach studded with giraffes is mentally stickier than a beach littered with starfish.

“The mind prioritizes remembering things that it is not able to explain very well,” said Ilker Yildirim, an assistant professor of psychology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and senior author of the paper. “If a scene is predictable, and not surprising, it might be ignored.””

This got me thinking about the many ways this rule applies to art— and how we can use it to make our writing more memorable. So that’s what I decided to explore in this week’s post.

Read the full post in MFA Lore on Substack by subscribing HERE

The 3 M's That Forecast a Bestseller

.jpg)

Hi Everyone,

This past week I had the privilege of chatting with several senior editors and publishers from major houses in NY. All were interested in the new book I’m ghosting and, while I can’t tell you anything about our specific project, I did pick up an editorial formula that might interest you. It’s how one publisher predicts which books will be bestsellers.

Subscribe and read the full article HERE!

Power Up Your Passive Protagonists!

Hello everybody,

Here's the latest from my MFA Lore newsletter on Substack

I’m back in the MFA archives again, mining gems that could bring value to your writing life. Today’s diamond in the rough is a letter about passive protagonists that I wrote to one of my most talented MFA advisees. With her permission, I’m going to share pertinent sections of this letter with you because, over the years, I’ve found that many, if not most of us, unwittingly hobble our protagonists in the inception. Activating them, then, becomes a priority in revision.

This advice is geared primarily toward fiction writers, but I urge memoirists to take note, too. When we write our own stories, we need to cast ourselves as active narrators, plunging into the past to rescue buried truths. There’s nothing passive about that role, yet it can be difficult to see and write ourselves onto the page in a truly active voice.

Passive protagonists and narrators are especially common in the work of female writers born into generations that discouraged or prevented women from speaking up, acting on their desires, and fighting for their rights. Women who were raised to hold themselves back, to mind their tongue, suppress their desires, and behave like “ladies,” could be forgiven if they struggled to speak their minds and demand the attention they deserved. For more than a century, then, the muted struggle between expression and restraint supplied the dramatic tension at the heart of fiction like Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Sylvia Plath’s The Belljar, and Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse. But interest in such straitjacketed characters has waned in the era of Olive Kitteridge, Lisbeth Salander, and Hermione Granger. And that’s a problem for writers like me.

Visit MFA Lore @Substack to read the whole articleIntricacies of POV

This is the biweekly writers’ Q&A from the MFA Lore section of Aimee Liu's Legacy & Lore newsletter @Substack.

Become a paid subscriber HERE to read the whole Roundup.

Welcome to our second Roundup, everyone!

I appreciate this week’s terrific questions. I’m in the thick of these same issues with my own work, so it was good to give them a bigger think here.

Before we plunge in, please remember that writing is a game that requires us to break as many rules as we observe. Prescriptions are for pharmaceuticals, not literature. So, while these answers reflect my literary preferences and experience as an author and teacher, they’re only my advice. Never forget that you are the author of your work, so the ultimate decision for what goes on in your pages lies with you.

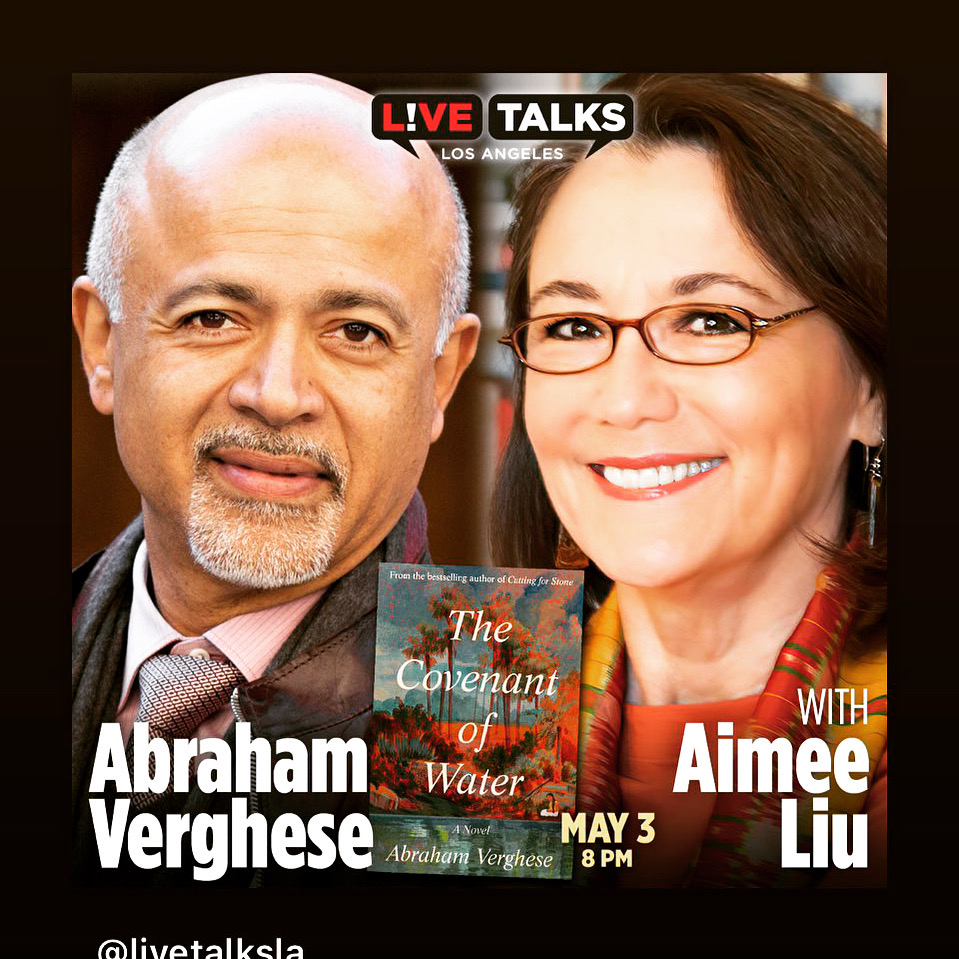

A book promotion 101 lesson from Oprah herself

You know what they say about best laid plans? Well, that goes double when Oprah calls. Even when she doesn’t call you.

Last week I was thrilled to be asked to “chat” onstage with novelist and physician extraordinaire Abraham Verghese for the series Live Talks Los Angeles. Though I’d never before met him, I’d loved Verghese’s first novel, Cutting For Stone, when it came out a decade ago. I’d traveled in Kerala, India, the location of his new novel, The Covenant of Water, and I’d written two novels of my own about India during the same turbulent colonial period when most of this story takes place. So I knew we’d find a lot to talk about.

I’ve interviewed others for Live Talks, including Aimee Tan and Pico Iyer. I prepare diligently for these events, both as a sign of respect for the authors and also as the best strategy for managing my own stage fright before large audiences. For this conversation I needed to inhale all 724 pages of The Covenant of Water inside of a week. I had to get cozy with more than 30 key characters and their masterfully interwoven plot lines. I needed to absorb the whole multi-generational saga so I could discuss its vast scope and humanity in detail. Or so I thought.

What I didn’t know was that The Covenant of Water would be selected for Oprah’s book club the week of our chat. And what I didn’t factor into my preparation was the fact that we’d be discussing the novel just one day after its publication date.

The subconscious has its own way of saying goodbye

My mother died one year ago today, yet she remains deeply present in my life — largely through our dreams together, which seem to be multiplying. Most of these nocturnal reunions skip into oblivion as soon as I wake. When a dream is particularly vivid, though, I try to scrawl its contours in my dream journal.

Still half asleep in the dark, I’ll write blind before the movie in my mind flickers out. And somehow, these half-conscious scribbles are surprisingly decipherable. Like hieroglyphics, they provide just enough imagery — stairs, foliage, faces, signs — to bring the mental story right back to me. In this way, the recent dreams involving my mother have re-emerged like prose-poems from the subconscious — or some other metaphysical zone. Consider this one:

I’m back in my childhood neighborhood with Mom as my guide, photographing all the old houses before they’re gone. She reminds me who lived in which glass house. The O’Neils. The Steinmetzes. The Bigelows and Barkentins. All now gone, though she is here. We trudge through the woods, needing to catch up, to explore, to remember where the Amusement Park is before it, too, is gone.

Yung Wing, my grandfather, and the seeds of China’s pro-democracy movement

Not many people today give much thought to the activists who first introduced the notion of democracy to China. So many political, economic, and military convulsions have since gripped the Middle Kingdom that the idealism of those early revolutionaries now seems both quaint and tragic. But they were every bit as brave, hotheaded, and patriotic in their time as the college students who dare to oppose Xi Jinping today.

For those who are following China’s pro-democracy movement, I offer this annotated extract from my grandfather’s memoirs, in which he meets an even earlier godfather of democracy in China, the 19th-century diplomat and Yale graduate known in America as Yung Wing:

My grandfather begins:

In 1901, after I was implicated in the T’ang Ts’ai-ch’ang case [the plot to blow up the armory], I fled to the safety of Shanghai. There my friend who had just returned from Japan, invited me to accompany him to Hong Kong to meet the famous Jung Ch’un-fu, who was known in America as Yung Wing.

It startled me when I first read this name in my grandfather’s book. I’ve been fascinated by Yung Wing for years. He was the first Chinese person ever to study in America; he graduated from my own alma mater, Yale, in 1854. After that he shuttled between America and China to champion better relations between the two countries, and in 1872 he launched the Chinese Educational Mission, which brought more than one hundred Chinese boys to study in New England. Yung Wing had an American wife, as did my grandfather, but this passage was my first notice that they personally knew each other.

Read original article on Medium HERE.

My Father's Secrets, Decoded at Last

My father was his family’s gatekeeper. Born in Shanghai in 1912, the eldest of his biracial siblings, he was raised to straddle East and West. He kept the peace between his Chinese father and American mother. And as the one member of his family who corresponded with those he’d left behind after moving to America in the 1930s, he alone held the secrets that could wound, shame, and inflame the relatives who’d immigrated with him.

Those secrets lay buried in the mass of junk that Dad hoarded throughout his life. After he died in 2007, I took the lead in curating this tangled mess. Both as a writer and as his daughter, I was fascinated by the mystery surrounding my remote, taciturn father. I hoped that in all his stuff, I’d discover the reasons why he claimed to remember so little about his past in China. Fifteen years later, I’m finally beginning to decode the evidence he was shielding.

This story originally posted @Medium HERE

Yellowface in the Family

I was cleaning out my father’s office after his death when I discovered the history of his movie years, stuffed into a soft red and gold Moroccan leather folio. This trove of yellowing newspaper clippings and gauzy headshots thrilled me. Here at last was the archive that would help me piece together Dad’s unlikely acting career 70 years earlier.

He’d never wanted to talk about his Hollywood days. MGM’s 1937 version of The Good Earth was the only movie he’d admit to being part of, which was odd because he hadn’t even made the final cut. His appearance as one of the uncles in the opening scene wound up on the editing room floor. He also worked as a technical consultant for the crews that shot in China. Dad had grown up in Shanghai, the son of a Chinese official who’d remained in Nanking after Dad’s American mother moved the rest of the family to California. My father doubtless was very useful to the production, given the various wars and political intrigues that were brewing in China at the time, but this role, too, was uncredited.

Not until late in his life, just a few years before he died, did I learn that both Dad and his sister Lotus performed onscreen with some of the biggest movie stars of the 1930s. On an idle whim, my brother had searched for their names on IMDb. According to his listed credits, our father, Maurice Liu, played the Hawaiian bridegroom in Waikiki Wedding, starring Bing Crosby. In Shadow of Chinatown, a Bela Lugosi vehicle, Dad appeared as a house boy. In West of Shanghai, with Boris Karloff, he was listed as a train conductor. Lotus had nine films under her name.

For Writers Especially: How to Manage Research Rapture

I once heard the late novelist Oakley Hall describe “research rapture” as an occupational hazard of fiction writing — one that too often consumes both writers and their work. I knew precisely what he meant. It’s easy for me to get so enthralled in the hunt for details about, say, midget submarines in WWII, that I fail to notice how much of the information I’m collecting serves absolutely no purpose in my novel.

Research rapture can cost you time and send you off on complicated tangents that will muck up your story and leave you stranded in a swamp of fascinating but irrelevant details. How to negotiate that edge between enough background information… and infinity? Here are 6 tips that have helped me maintain a productive balance while writing my historical novels.

Read the original article on Medium @HumanParts HERE."Like Singing a Song" About the Most Magical Father I Never Met

Read the original article on Medium @HumanParts HERE.

Family Photos Can Change You

Lucky for me, my father was a packrat. Dad spoke little about his childhood in China during the Warlord Era, but he kept suitcases full of artifacts, most of which only surfaced after his death in 2007. Among these mementos, I discovered photographs that swept me back in time and introduced me to relatives who belonged to a lost world.

At a glance, these fading images seem like curiosities in a museum, so antiquated that they couldn’t possibly connect to life on Earth today. But to me, their faces have the haunting power of ghosts. They beckon me closer, hold me longer, and keep drawing me back. “We are your people,” they seem to say. “We are your kin, your tribe. We belong to you and you to us.”

Read the original article with all photographs @Medium Human Parts HERE

Code Talking: An Excerpt from Glorious Boy

.jpg)

During World War II, thousands of women were employed by the Allies as code breakers both in Europe and across Asia. In the Pacific Theater, the U.S. Marine Corps also recruited some 500 Navajo code talkers to transmit messages in their native language, because it was unintelligible to the Japanese. In my WWII novel Glorious Boy, Claire Durant volunteers to use her knowledge of indigenous languages to both break and make codes for the British in Calcutta in 1942.

The Primal Power of Stories That Evoke Yearning and Dread

About Me-- Aimee Liu

I recently discovered the Medium publication, About Me. Its whole m.o. is introducing writers, and it occurred to me that this might be a good addition to my blog, so here goes!

Full article @ authoraimeeliu.Medium.com

P.S. If you join Medium, your $5 monthly membership fee directly supports Aimee Liu and all the other writers you read. You'll have full access to every story on Medium. Join us HERE!

How Creative Generosity Can Prevent Loneliness

Pathos and Bathos in “The Crown”