Is Your Child a Late Talker? The reason might be Einstein Syndrome

Little Albert Einstein was a handful. He threw tantrums, resisted potty training, ignored anything or anyone he found boring, and didn’t speak his first word until the age of three. His parents (remember, this was the 1880s) feared he was “mentally retarded.” His teachers despaired of his ability to learn. He still had difficulty talking at age nine.

In all these respects the world’s most famous genius resembled other brilliant thinkers, such as physicists Edward Teller and Richard Feynman, musicians Arthur Rubenstein and Clara Schumann, and the Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker. Today there’s a name for the pattern of development that all these extraordinary people shared as children: Einstein Syndrome.

Was Einstein on the spectrum?

Vanderbilt U. Professor Stephen Camarata was himself a late talker. His son was a late talker. And as a doctor of speech science, Camarata now conducts research on speech delay, which, he says, is too often attributed to autism.

What’s important for parents to remember is that, while most children with autism are late talkers, most late talkers do not have autism. Alas, this distinction is often lost on doctors and other clinicians who diagnose autism without fully exploring other possible causes of speech delay. This error can lead to needless pain and heartache for families of bright, healthy children whose late talking is actually a sign of mental precocity in mathematical, musical, and analytic thinking.

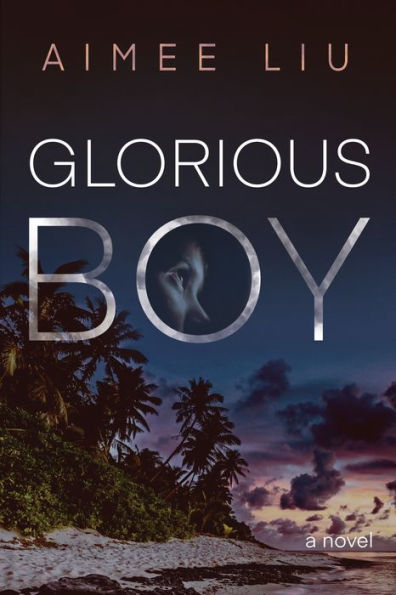

I began researching Einstein Syndrome for my novel Glorious Boy, which focuses on a four-year-old late talker in the 1940s, when speech delay was still regarded as a sign of “retardation.” The confusion and pain that this misunderstanding often caused plays a central role in the story. Unfortunately, as I learned when a child in my own family was speech delayed, this symptom still can cause needless worry.

Otherwise engaged

Parents of young children are forever checking to make sure that their child’s development is “normal.” Pediatricians use percentile graphs to measure growth, skills, reflexes, and — yes — language ability as a gauge of healthy development. When a child “fails” to speak even a few words by age two, it’s naturally concerning.

It’s worth remembering, however, that language isn’t our only, or even our primary, means of communication. Emotional connection doesn’t depend on speech. Body language, eye contact, touch, and shared activities and experiences, such as music, also bring us closer together. These different forms of attunement can be key to understanding the mind of a child with Einstein Syndrome.

While it’s not known exactly why these kids are slow to talk, the likely explanation is that their brains are simply preoccupied with other more urgent business. I saw this firsthand when my great nephew was little. He could watch a prism for hours, studying the color beams and refractions of light, discovering cause and effect as he silently moved the prism in and out of the sun. He also loved plants and sound. He needed no one else to entertain him and was not much interested in company. The world itself kept him fully occupied, and his second birthday passed without a word.

At three, that changed. By four, he was talking up a storm, but certain aspects of his earlier development remain in evidence six years later. His current fascination is botany. He spends hours in the woods, studying geology, flora, and fauna, memorizing scientific names and filtering conversation through this passion: “What are your favorite animals? What are your favorite plants? Why?” He has the preoccupations of a scientist.

Another language

Will my great nephew turn out to be a genius like Einstein? I have no idea. But he’s an interesting child with rare curiosity and independence. He’s highly self-directed with clear passions. Far from being a worry to his parents, he’s a comfort and an ever-surprising delight. Above all, he’s his own person.

And that’s the beauty of kids like Einstein. They don’t care what others think. They won’t worry about conforming or not conforming. They’ll find their own way without a lot of anguish — as long as others don’t try to change or block their passions.

They’ll also find their own language. Some of these children are born musicians. Their language might be piano or the violin, or conducting an orchestra. Others are scientists who naturally learn to think in physics, chemistry, or biology. Still others are mathematicians who communicate in numbers. Get on their wavelength, and you get to go along for the ride.

Check your concerns

None of this is to suggest that you should “just wait and see.” As Dr. Camarata reminds us, there are many possible reasons why a child is late to talk, and it’s important to have your child evaluated early if there is a delay. But it’s also important to educate yourself. He tells the cautionary tale of his own experience:

When my son was labeled as having mental retardation (now called intellectual disability), I asked the psychologist why she believed that he would learn much more slowly than other children. It turned out that the test she was using was based upon his speaking and listening ability and not actually on his ability to think or to reason. So, the mislabeling of my son was directly due to misunderstanding the diagnostic process for late-talking children.

Remember that you know your child best. Trust your instincts and your common sense.

For a portrait of a child with Einstein Syndrome, read this article:

For even more about Einstein Syndrome, read the book that started this conversation, The Einstein Syndrome by Thomas Sowell:

If you’d like to read my novel about a child with Einstein Syndrome, please pick up Glorious Boy: